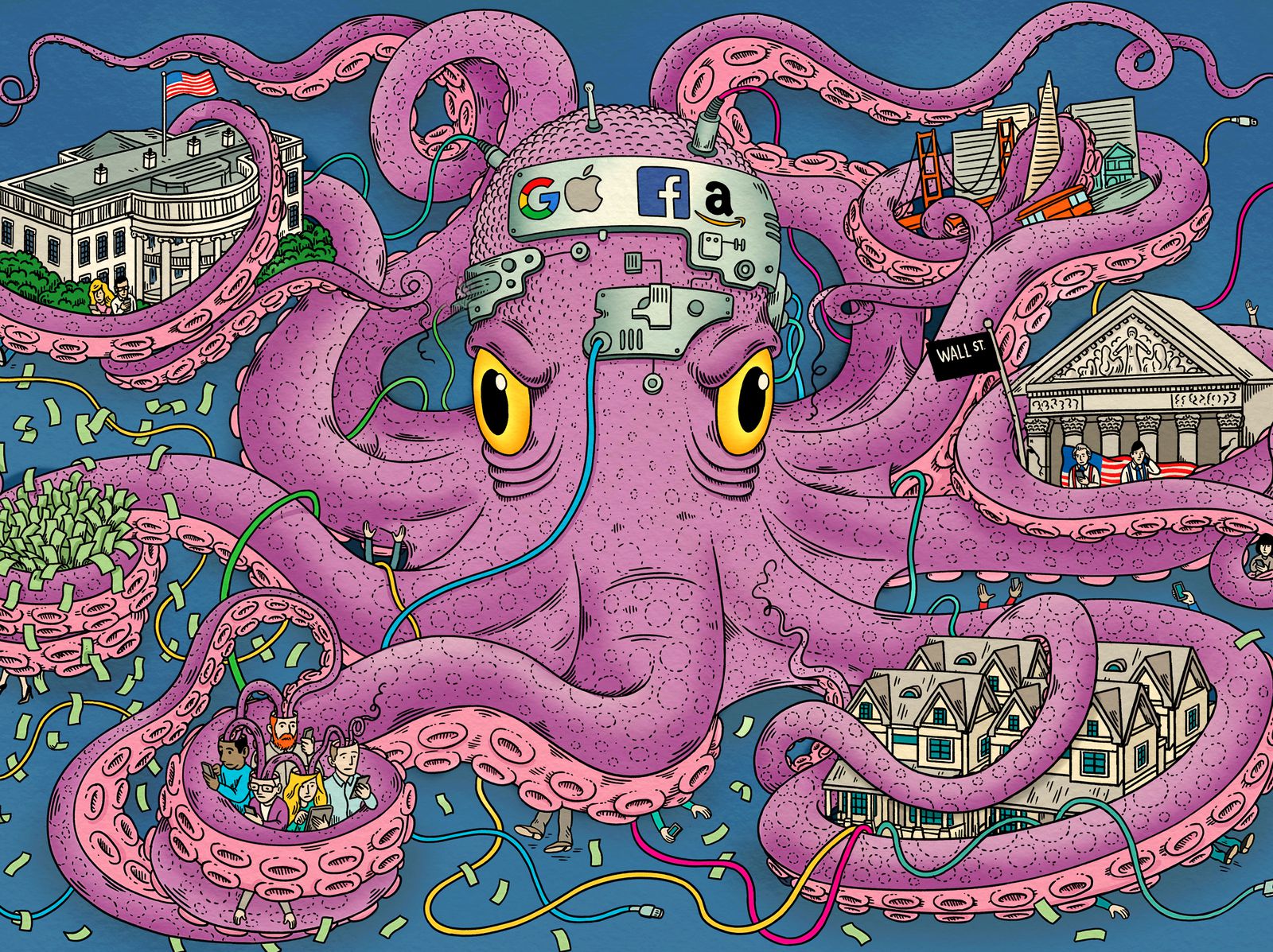

I repost Ted Gioia’s Substack post here because I couldn’t have said it all better myself. As he outlines it, this has been tuka‘s approach all along. The one thing he doesn’t address is the winner-take-all aspect of creative markets – why all these YT revenues end up going to a few mass influencers or curators. Blockchain and tokenization are necessary tools to decentralize and distribute rewards for value created.

By Ted Gioia

“Victory is assured!”

I’m talking about victory for creative professionals—musicians, writers, visual artists, and others who have been squeezed by the digital economy.

You’re probably surprised. Some people think I’m the Dr. Doom of the music scene. And it’s true, I’ve made a lot of depressing predictions over the last few years, Even more depressing, many of these predictions have already come true.

I’ve told horror stories about musicians who lost their gigs during the pandemic, and also saw their music royalties collapse as the audience shifted to streaming. I’ve talked about journalists fired from downsizing newspapers. And filmmakers who can’t get funded to make a movie unless a Marvel superhero is named in the title .

But now I want to tell you the rest of the story. Because the next phase in the cycle is filled with good news.

Victory is assured.

Let’s start by looking at the music business, where the squeeze has been the worst.

Whenever I do a forecast, my first step is to follow the money. And the adage that money talks has never been truer than right now. Those dollars are telling an amazing and unexpected story. Word on the street is that record labels are offering far more attractive terms to musicians than ever before.

“Here’s my craziest prediction. In the future, single individuals will have more impact in launching new artists than major record labels or streaming platforms.”

In the old days, musicians were lucky to get 15% of revenues, but I’m now hearing increasingly about deals that give artists a 50% cut, and in some instances allow them to regain ownership of their master recordings at a future date. The music moguls are positively generous—and (as we shall see) for structural reasons in the business that aren’t going away.

And it’s not just major labels giving more money to musicians. Take a look at Bandcamp, which lets musicians collect almost 90% of revenues from vinyl sales. And I’m hearing constantly from techies and entrepreneurs who are working on similar artist-centric business models. We are only in the early innings of this new game, but the shift is already enough to force huge concessions from legacy music companies.

Artist-friendly platforms are the future of music. And other creative pursuits as well—my own platform, Substack, is also allowing creators to keep close to 90% of revenues. This has spurred a huge talent migration from old media, and not merely for writers—you can find almost every kind of creative professional on Substack, from cartoonists to photographers.

For 25 long, hard years, creative professionals have been told that you must give things away for free on the Internet. But not anymore. Alternative economic models are not only emerging, but are propelling the fastest-growing platforms in arts and entertainment.

This is not only shaking up highbrow and popular culture, but capturing the attention of the next generation of tech visionaries—which is why, in the last year or so, I’ve been constantly approached by startups asking me to evaluate their business plans. This is unprecedented. It simply didn’t happen before the pandemic. But not only are these entrepreneurs trying to figure out what artists want, but they’re actually relying on creator wealth maximization as the focal point for their businesses.

In general, these young techies are smarter than the folks running the music business right now. (That’s a subject I want to discuss at a later date—I call it my ‘idiot nephew theory’ of the music business. But it has to wait.) Of course, many of these entrepreneurs are dreamers who will never go anywhere. That’s always the case with entrepreneurs. But some will succeed, and in a meaningful way.

In fact, it’s inevitable—and for the simple reason that the old institutions have stopped investing in the future. The new guard will take over because the old guard got weak and lazy.

Why is all this happening? Let’s go back to look at the music situation, because this helps us understand the larger picture.

Record labels are getting more generous because they don’t have a choice. They destroyed their own power base and source of influence. They stopped investing in R&D and new consumer technologies back in the 1980s. Twenty years later, they stopped manufacturing and distributing physical albums—and even when vinyl took off, they were asleep at the wheel. Over the same time period, they lost their marketing skills, trusting more in payola and influence peddling of various sorts.

But that’s just a start. Over a fifty-year period, record labels relentlessly dumbed-down their A&R departments. They shut down their recording studios, and let musicians handle that themselves—often even encouraging artists to record entire albums at home. Then they let huge streaming platforms control the relationship with consumers. At every juncture, they opted to do less and less, until they were left doing almost nothing at all.

The music industry’s unstated dream was to exit every part of the business, except cashing the checks. But reality doesn’t work that way. If you don’t add value, those checks eventually start shrinking.

The simple fact is that the legacy music business is living off the past—and will continue to do so until the copyrights expire. For a few more years, they will collect royalties on old songs, and make money on reissues and archival material. They know themselves that they have lost control of the future of music. That’s why, if they have spare cash, they use it to buy up catalogs and publishing rights of music from back in the day. Their favorite artists are dead artists.

But this is not a long-term game. It’s a death wish.

The major labels would like to own the music stars of the future, but they won’t. They would like to act greedy and put the squeeze on the next generation, but they can’t. They simply don’t have the leverage. And never will again.

And who will win if record labels lose? You think it might be the streaming platforms? Think again—because that’s not going to happen. Spotify and Apple Music are even less interested than the major labels in nurturing talent and building the careers of young artists.

Here’s my craziest prediction. In the future, single individuals will have more impact in launching new artists than major record labels or streaming platforms.

Just consider this: There are now 36 different YouTube channels with 50 million or more subscribers—and they’re often run by a single ambitious person, maybe with a little bit of support help. In fact, there are now seven YouTube channels with more than 100 million subscribers. By comparison, the New York Times only has nine million subscribers.

“How could a Substack column outbid major media outlets for new talent? But not only can it happen, it will inevitably happen.”

Most people don’t stop and think about the implications of this. But just ponder what it means when some dude sitting in a basement has ten times as much reach and influence as the New York Times.

If you run one of these channels and have any skill in identifying talent, you can launch the next generation of stars.

And not just in music. This works for everything—comedy, dance, animation, you name it.

Consider the case of MrBeast. Many of you have no idea what I’m talking about, but you need to find out—because MrBeast (or people like him) are going to change popular culture, whether we like it or not. MrBeast, for a start, runs 18 YouTube channels with more than 200 million total subscribers. He now has his videos translated into four languages: Spanish, Portuguese, Hindi, and Russian.

What does he do? I’m no expert on MrBeast, but I’m told he’s a good dude, and gives away a lot of money—huge sums, to be blunt. And he can afford to do it, because YouTube channels are low-overhead operations with enormous cash generation potential.

Oh, I forgot to mention that MrBeast is looking to raise capital from financial investors. He claims that his business is worth $1.5 billion, and may sell 10% to get $150 million to fund his future plans.

I’m not even beginning to pretend that MrBeast will use this money to get into the music business. But he might. And if he doesn’t, someone else like him will.

MrBeast has got the cash to shake up the music business—and if he doesn’t, someone like him will

I note that MrBeast only ranks number five in YouTube channel subscriptions. There are other people like him, or will be soon, and they are much better equipped to launch a new music act than any of the major labels.

That’s why musicians can make more money when the distribution model shifts from bloated record labels with huge overhead to alternative web-based platforms. I expect that deals for artists on these web channels will be more like 50/50. MrBeast is known for his generosity, but even if he wasn’t, his business model is much more flexible than anything Sony or Universal Music could ever dream of. These new platforms can afford to offer better terms to creators, and almost certainly will—because if they don’t someone else will.

This didn’t take place during the first wave of YouTube channels, because these influencers (I hate the term, but it’s appropriate in this setting) were focused on making themselves into money-making stars. But the next phase of growth for these people is brand extension, and that’s going to turn them into talent scouts.

I’m focusing on YouTube channels here, but the same story could be told about podcasters—or any other individual with a lock on an audience in the tens of millions. Consider them as the equivalent of the Ed Sullivan Show in the old days. The host of this long-running TV show didn’t have much talent himself, but it hardly mattered—Ed Sullivan was the curator who introduced America to Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and other rising stars. That kind of thing will happen again, but via a web channel or alternative platform.

These individuals can do absolutely everything a record label currently does, and do it better—they can launch new stars, get them instant visibility and gigs, generate millions of views for new songs, attract endorsement deals, etc. The few things they can’t do in-house (for example, press vinyl records) can be easily outsourced.

The same thing will happen in publishing. I’m already seeing a few of the more popular Substack writers using their huge subscriber base to launch the careers of other writers. By my calculations, this can be even more profitable and impactful than a book contract with a New York publisher—benefiting both the sponsoring writer and the new talent.

In fact, I might move in this direction myself. It’s too early, but 2-3 years from now I might start scouting out talented young writers or podcasters and feature them here in The Honest Broker. Everything depends on subscription numbers, but it’s possible that I could pay better than the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal.

At first blush, this seems impossible. How could a Substack column outbid major media outlets for new talent? But not only can it happen, it will inevitably happen. It’s the same story as in music. The old guard has stopped defending its base business, and everything is either up for grabs now—or will be very soon.

Newspapers have lost enormous power over the last twenty years. They have lost subscribers. They have lost ad revenues. They have even, in many instances, lost credibility and respect. Up until now, this has hurt writers—who depended on the newspapers for assignments and pay checks. But we are now arriving at the point where the trend reverses.

And this reversal opens up huge opportunities and income potential for smarter, nimbler operators.

I could give many other examples. What I’m describing is also true for Hollywood movie studios, book publishing, and every other field where the old guard has become arteriosclerotic and inflexible.

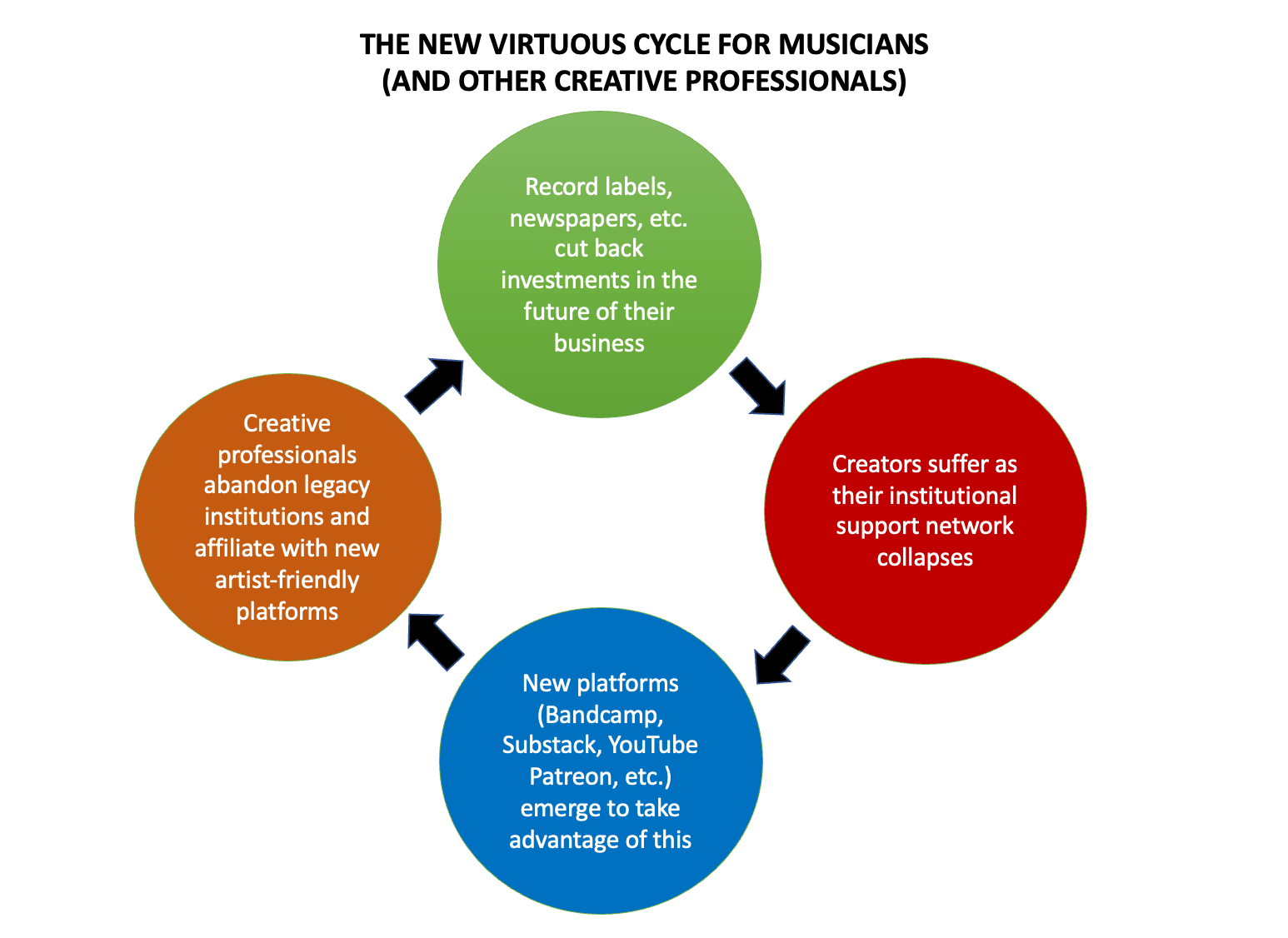

Okay, let me summarize the whole thing in a diagram.

[Note: tuka is in the blue circle here.]

[Note: tuka is in the blue circle here.]

There’s an elegant irony here. The very same forces putting the squeeze on creators actually serve to accelerate the happy next phase.

This is one reason why I believe karma is at work in the universe. If you run a business that depends on creativity, you can’t punish the creators without consequences. Sometimes it takes a while for the cycle to play out, but it always plays out the same way.

There are many aspects of this story I haven’t covered here. There are all sorts of Web3 angles, and there’s also a story to be told about how platforms such as Spotify will pay a price for squeezing musicians to subsidize their entry into podcasting and other ancillary businesses. But we can look at those on another occasion.

For the time being, I just want you to keep your eyes on the prize. And remember—Victory is Assured!